It’s December 21, 2022. I’m recovering from COVID and am finally able to leave isolation in my bedroom today. But now child #4 is sick. And child #1, who doesn’t live at home, is sick and says he might wait until after Christmas to visit. Disappointed, he said he was preparing for “Scuffed Christmas 2.0”.

Why 2.0? Last year, Christmas 2021, our oldest son suspected he had COVID, and therefore he spent the holiday isolating, and we opened presents socially distanced using Face Time. But really, this year should be Scuffed Christmas 3.0, because Christmas 2020 was no dream holiday. That year, my daughter and I spent Christmas Eve and much of Christmas day away from home, caring for my father who had just been released from a week long stay in the hospital. Oh, and during that stay, he was diagnosed with stage 4 colon cancer.

For those of you older than 25, the “kids” use scuffed as an adjective that means “of poor standards or low quality” or to refer to something broken or not working as intended. (Thanks, Urban Dictionary.) Yep, that definitely could be our Christmas 2022.

Which is too bad, because everything is perfect at Christmas, right? I mean, the lyrics of “Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas” tell us every year to “Let our hearts be light” because “from now on our troubles will be out of sight.” I strongly dislike that song. Because it’s a lie. Troubles are a part of this life. I experienced many a less than perfect Christmas growing up. Like, when my parents fought, and the tension hung so thick at the dinner table that I could hardly swallow my food. When my mom cried over frustration of being stuck in her wheelchair. Then there was the Christmas we had to put her in a nursing home.

As the Man in Black tells Princess Buttercup, “Life is pain, Highness. Anyone who says differently is selling something.”* “Have yourself a merry little Christmas” is selling us an unrealistic picture of the holiday, pretending that troubles don’t shadow us just because it’s December. But many of us are facing loss and grief and pain, no matter the season. I have several friends caring for aging parents and facing difficult decisions. Several who are grieving loved ones. My husband’s aunt just got diagnosed with cancer and started chemo the first week of December. And think of the poor people in Ukraine.

I’m not a Scrooge. I am just pointing out from the midst of tinsel and twinkling lights that Christmas can be hard as well as merry. That people are struggling and sometimes the notion of a perfect Christmas makes it worse.

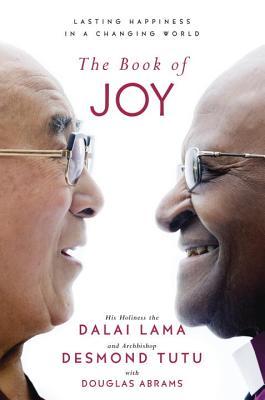

But we can and should find comfort in Christmas, even if it is scuffed. We should find our joy not in gifts or chocolate or decorations, but in the reason we celebrate in the first place. Good will conquer evil. Love is meant for all. And salvation comes to us in simple, humble ways, like a naked baby in a barn. We can face our troubles with hope, because we are eternally cherished. And in turn, we can cherish and support each other.

For our family this year, Christmas might not look like it has in the past, or it might not be perfect, but we will still find time to enjoy each other and share love with each other. To find moments of joy. As I told my oldest son, Christmas is a season. We can celebrate on any day, not just December 25.

Wishing you the very best this holiday season, even if it is “scuffed.” Especially if it is!

*If you don’t recognize this quote from The Princess Bride, then go watch it now! That will make you smile! 🙂

Find joy!