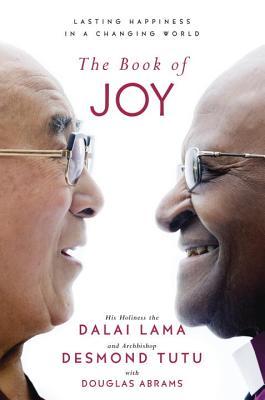

I’m desperately trying to figure out how to bring more happiness into this world. I’m looking everywhere- the Bible, Buddhism, Kelly Corrigan, Reasons to Be Cheerful, and books, including The Book of Joy: Lasting Happiness in a Changing World. This wonderful book is a collection of interviews between two spiritual giants, the current Dalai Lama, a Buddhist in exile from Tibet, and Archbishop Desmond Tutu, a Christian from South Africa. Both men have insightful things to say about happiness, suffering, loss, and what we need to do to get along better. I highly recommend. It’s not religious, it’s spiritual, and a much needed read at this time.

Regarding happiness, the Dalai Lama and the Archbishop agree we need to think less about ourselves and spend more time thinking about others. The Dalai Lama says:

The only thing that will bring happiness is affection and warmheartedness… We are social animals, and cooperation is necessary for our survival, but cooperation is entirely based on trust. When there is trust, people are brought together– whole nations are brought together. When you have a more compassionate mind and cultivate warmheartedness, the whole atmosphere around you becomes more positive and friendlier… With too much self-focus your vision becomes narrow, and with this even a small problem appears out of proportion and unbearable.

The Dalai Lama, The Book of Joy by Douglas Abrams

I feel like, at least in America, we are definitely thinking about ourselves A LOT. My social media posts, my freedoms, my rights, my sacrifices. Concern for others often falls low on the collective priority list. No wonder we are currently flooded with anxiety, anger, and distrust.

The etymology of kindness

The Dalai Lama is definitely onto something, especially when we look at the etymology of kindness. According to the Online Etymology Dictionary, kindness derives from the Old English word kyndnes which meant “nation,” also “produce, an increase.” It also has roots in the word kin, as in one’s family, race or relations, as in “friendly, deliberately doing good to others,” from Middle English kinde, from Old English (ge)cynde “natural, native, innate,” originally “with the feeling of relatives for each other.” By the 13th century, kindness came to mean “courtesy, noble deeds, kind feelings, and the quality or habit of being kind”.

Do you notice what I do here? The word kindness is rooted in our relationships with others (feeling of relatives for each other) and our nation. Happiness cannot be achieved by focusing merely on me. We need more we, less me. We will all enjoy more happiness when we all do a better job of thinking of the collective we, of embracing kind feelings, and exhibiting kind habits.

How do you see kindness around you, and what do you do to share it?

And please consider getting a copy of The Book of Joy. My friend Lynne says the audio book is done very well.

Thank you to Joseph Terrell for inspiring this look at the etymology of kindness (check out his comment here) and Online Etymology Dictionary, Macmillian Dictionary Blog, and Speak Media for information about kindness.

Thanks for being kind with me!

Another good post and an example of why yours is the only blog I follow. I do not recall how I came across your blog, but no doubt, the very name of it caught my eye, for I love language – the very concept of it. I love to discover why words mean what they do and a how they came to mean what they mean. As a preacher, language is the primary tool of my trade, and just as the quality of any craftsman’s work depends in large measure on the quality of the tools at his disposal, the quality of my work depends, in great measure, on the quality of the language I use. I do not know how much it benefits my congregation, but in my sermons, I often refer to the words as they appear in the original Hebrew of the OT and Greek of the NT. I do not do this in order to give people the impression that I have a superior intellect. In fact, my understanding of the original languages of the Scriptures is quite basic and I rely on reference works to provide me with the more detailed information. (I am so glad that I live in the internet age when all these reference works are so easily available.) But being able to see the Scriptures in their original languages provides some insights that might otherwise be missed. Moreover, some of the errors that people cling to (and sometimes get quite forceful in their defense of) arise from relying either on a poor translation or simply not taking into consideration the wide variety of meanings and uses a word can have. Much of my preaching consists of untangling the linguistic mess that many create through a misunderstanding of words.

I have thoroughly enjoyed these two posts of yours on kindness. I think it was Glen Campbell who sang a song with the lines, “And if you try a little kindness, Then you’ll overlook the blindness, Of narrow-minded people on the narrow-minded streets.”

In this post, you brought up the point that kind referred to nations. I had forgotten that point. On one occasion when I was studying English words that have the Greek “gen-” root in them, I was surprised to see that “Gentile” is among them. It was through Latin that it came to mean the same thing as the Hebrew “goy” – a non-Jew. From early times in Hebrew history, the Jews viewed the world as made of Jews and non-Jews and the non-Jews were “the nations.” When one sees the word Gentile in the NT, it is a translation of the Greek word “ethnos” from which we get ethnic, a reference to one’s national origin.

In looking at the etymology of Gentile (which by its gen- root is connected to “kind”), I thought it ironic that our word “kind” shares a common source with a word that has been most unkindly used. As I read on the etymology of Gentile, it appears that it has never been used in a positive sense; it always had the sense of “the others,” and that in the sense of “others who are not as good as us.” Evidently, there was a time when Christians used Gentile to mean “non-Christian, pagan, heathen etc.” Mormons and Shakers also used it to describe all of those outside of their particular group.

But one aspect of kindness is to recognize that we are all of the same group – humans. As I have looked at the origin of these words, it is plain to see how our racial tensions arise from a lack of “kindness,” a failure to recognize that, despite some differences in appearance and culture, we humans are all of one kind. And the best way to prove that one believes that is to show kindness to all humans, regardless of the superficial differences among those of the kind called human.

BTW, the Greek word behind “kindness” in the list of the fruit of the Spirit is not one of the gen- root Greek words. Rather, it is derived from a word meaning “useful, profitable, well fit for use.” This does not take away from anything we have said about kindness being related to words indicating “of the same kind,” but it adds to the abstract concept of kindness the concept of usefulness. To be kind is to be useful, to actually fulfill the needs of others. Sometimes this can be done with just kind words, for words are powerful and can heal a wounded soul like nothing else. But, in many cases, kindness must put on some work clothes.

I also found it revealing to look at the essential meaning of the next in the fruit of the Spirit: goodness. This is the definition I found in one of the NT Greek reference books I often use: “intrinsic goodness, especially as a personal quality, with stress on the kindly (rather than the righteous) side of goodness.” Unfortunately, most religious people are more consumed with being “righteous” than “good.” When righteousness becomes our primary or even singular goal, we become judgmental and begin to see those who do not fit our version of righteousness as “other,” – “Gentiles.” But if goodness (as herein defined) is our goal, we will act righteously, but we will do so in a way that is kind – that is, useful, helpful. And that is why the parable is not called “The Righteous Samaritan,” but “The Good Samaritan.”

Once again, forgive the length of this comment. But your writing inspires thought in me, and I count that a good thing. I read what you write, and it moves me to reference your sources and to look at some others as well, so I learn. And when I learn something, it is difficult, if not impossible for me to restrain myself from sharing it with someone!

Thank you! My pastor also frequently explains the original meanings of Biblical words, and I find it very helpful and interesting. Keep growing and giving! 🙂